What Does It Mean To Animate On Twos

The bouncing ball blitheness (beneath) consists of these six frames, repeated indefinitely.

This animation moves at 10 frames per 2d.

Animation is a method in which figures are manipulated to appear equally moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by paw on transparent celluloid sheets to be photographed and exhibited on pic. Today, nigh animations are made with computer-generated imagery (CGI). Computer animation tin be very detailed 3D animation, while 2nd computer animation (which may take the look of traditional blitheness) can be used for stylistic reasons, low bandwidth, or faster real-time renderings. Other common blitheness methods apply a stop motion technique to two- and three-dimensional objects like newspaper cutouts, puppets, or clay figures.

An animated cartoon is an animated picture show, usually a brusk film, featuring an exaggerated visual style. The style takes inspiration from comic strips, often featuring anthropomorphic animals, superheroes, or the adventures of human being protagonists (either children or adults). Especially with animals that course a natural predator/prey relationship (e.k. cats and mice, coyotes and birds), the activity oft centers around violent pratfalls such as falls, collisions, and explosions that would be lethal in real life.

The illusion of animation—every bit in motion pictures in general—has traditionally been attributed to persistence of vision and afterwards to the phi phenomenon and/or beta movement, but the exact neurological causes are still uncertain. The illusion of motion caused by a rapid succession of images that minimally differ from each other, with unnoticeable interruptions, is a stroboscopic upshot. While animators traditionally used to draw each part of the movements and changes of figures on transparent cels that could be moved over a separate background, computer animation is usually based on programming paths between key frames to maneuver digitally created figures throughout a digitally created environment.

Analog mechanical blitheness media that rely on the rapid display of sequential images include the phénakisticope, zoetrope, flip book, praxinoscope, and moving picture. Goggle box and video are pop electronic animation media that originally were analog and now operate digitally. For display on computers, engineering science such as the animated GIF and Flash animation were developed.

In addition to short films, feature films, boob tube series, animated GIFs, and other media defended to the display of moving images, animation is besides prevalent in video games, motion graphics, user interfaces, and visual furnishings.[1]

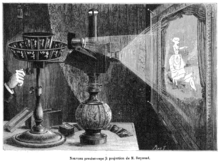

The physical motility of image parts through unproblematic mechanics—for example moving images in magic lantern shows—tin too exist considered blitheness. The mechanical manipulation of three-dimensional puppets and objects to emulate living beings has a very long history in automata. Electronic automata were popularized past Disney as animatronics.

Etymology [edit]

The give-and-take "blitheness" stems from the Latin "animātiōn", stem of "animātiō", meaning "a bestowing of life".[2] The primary significant of the English word is "liveliness" and has been in utilize much longer than the pregnant of "moving epitome medium".

History [edit]

Before cinematography [edit]

Nr. x in the reworked 2d series of Stampfer'due south stroboscopic discs published by Trentsensky & Vieweg in 1833.

Hundreds of years before the introduction of true animation, people all over the earth enjoyed shows with moving figures that were created and manipulated manually in puppetry, automata, shadow play, and the magic lantern. The multi-media phantasmagoria shows that were very popular in European theatres from the late 18th century through the first half of the 19th century, featured lifelike projections of moving ghosts and other frightful imagery in movement.

A projecting praxinoscope, from 1882, hither shown superimposing an animated figure on a separately projected groundwork scene

In 1833, the stroboscopic disc (better known as the phénakisticope) introduced the principle of mod animation with sequential images that were shown ane by 1 in quick succession to class an optical illusion of motion pictures. Series of sequential images had occasionally been made over thousands of years, but the stroboscopic disc provided the start method to represent such images in fluent motion and for the first time had artists creating series with a proper systematic breakup of movements. The stroboscopic animation principle was also applied in the zoetrope (1866), the flip book (1868) and the praxinoscope (1877). A typical 19th-century animation contained almost 12 images that were displayed as a continuous loop past spinning a device manually. The flip book often contained more pictures and had a starting time and cease, only its animation would non last longer than a few seconds. The showtime to create much longer sequences seems to have been Charles-Émile Reynaud, who betwixt 1892 and 1900 had much success with his 10- to 15-minute-long Pantomimes Lumineuses.

Silent era [edit]

When cinematography eventually broke through in 1895 subsequently animated pictures had been known for decades, the wonder of the realistic details in the new medium was seen as its biggest achievement. Animation on picture show was not commercialized until a few years subsequently past manufacturers of optical toys, with chromolithography pic loops (ofttimes traced from alive-activeness footage) for adjusted toy magic lanterns intended for kids to utilise at domicile. Information technology would take some more than years earlier animation reached movie theaters.

Afterward before experiments by movie pioneers J. Stuart Blackton, Arthur Melbourne-Cooper, Segundo de Chomón, and Edwin S. Porter (among others), Blackton's The Haunted Hotel (1907) was the outset huge stop movement success, baffling audiences by showing objects that plainly moved by themselves in total photographic detail, without signs of any known stage fox.

Émile Cohl'due south Fantasmagorie (1908) is the oldest known example of what became known as traditional (manus-drawn) animation. Other great artistic and very influential short films were created by Ladislas Starevich with his puppet animations since 1910 and past Winsor McCay with detailed drawn animation in films such as Little Nemo (1911) and Gertie the Dinosaur (1914).

During the 1910s, the production of animated "cartoons" became an industry in the Us.[three] Successful producer John Randolph Bray and animator Earl Hurd, patented the cel blitheness process that dominated the animation industry for the residual of the century.[iv] [5] Felix the Cat, who debuted in 1919, became the commencement animated superstar.

American golden age [edit]

In 1928, Steamboat Willie, featuring Mickey Mouse and Minnie Mouse, popularized film with synchronized audio and put Walt Disney's studio at the forefront of the animation industry.

The enormous success of Mickey Mouse is seen as the start of the golden age of American blitheness that would last until the 1960s. The United States dominated the world market of animation with a plethora of cel-animated theatrical shorts. Several studios would introduce characters that would go very popular and would have long-lasting careers, including Walt Disney Productions' Goofy (1932) and Donald Duck (1934), Warner Bros. Cartoons' Looney Tunes characters like Porky Pig (1935), Daffy Duck (1937), Bugs Bunny (1938–1940), Tweety (1941–1942), Sylvester the Cat (1945), Wile E. Coyote and Road Runner (1949), Fleischer Studios/Paramount Drawing Studios' Betty Boop (1930), Popeye (1933), Superman (1941) and Casper (1945), MGM cartoon studio's Tom and Jerry (1940) and Droopy, Walter Lantz Productions/Universal Studio Cartoons' Woody Woodpecker (1940), Terrytoons/20th Century Play tricks'southward Gandy Goose (1938), Dinky Duck (1939), Mighty Mouse (1942) and Heckle and Jeckle (1946) and United Artists' Pink Panther (1963).

Features earlier CGI [edit]

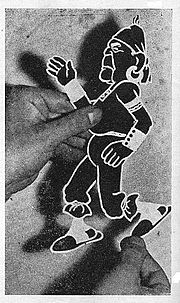

Italian-Argentine cartoonist Quirino Cristiani showing the cut and articulated figure of his satirical character El Peludo (based on President Yrigoyen) patented in 1916 for the realization of his films, including the world'due south get-go animated feature film El Apóstol.[half-dozen]

In 1917, Italian-Argentine director Quirino Cristiani made the outset feature-length film El Apóstol (at present lost), which became a disquisitional and commercial success. It was followed by Cristiani'southward Sin dejar rastros in 1918, but one day after its premiere, the film was confiscated by the authorities.

Later working on it for 3 years, Lotte Reiniger released the German feature-length silhouette blitheness Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed in 1926, the oldest extant animated characteristic.

In 1937, Walt Disney Studios premiered their outset animated feature, Snow White and the Vii Dwarfs, however one of the highest-grossing traditional animation features equally of May 2020[update].[7] [8] The Fleischer studios followed this example in 1939 with Gulliver'south Travels with some success. Partly due to foreign markets being cut off by the Second World War, Disney's side by side features Pinocchio, Fantasia (both 1940) and Fleischer Studios' second animated feature Mr. Bug Goes to Boondocks (1941–1942) failed at the box function. For decades after, Disney would be the but American studio to regularly produce animated features, until Ralph Bakshi became the first to also release more than than a handful features. Sullivan-Bluth Studios began to regularly produce animated features starting with An American Tail in 1986.

Although relatively few titles became equally successful as Disney's features, other countries developed their own animation industries that produced both brusk and feature theatrical animations in a wide multifariousness of styles, relatively often including stop motion and cutout animation techniques. Russian federation'southward Soyuzmultfilm blitheness studio, founded in 1936, produced twenty films (including shorts) per year on boilerplate and reached 1,582 titles in 2018. Prc, Czechoslovakia / Czech Republic, Italy, France, and Belgium were other countries that more than occasionally released feature films, while Japan became a truthful powerhouse of animation production, with its ain recognizable and influential anime style of constructive express animation.

Television [edit]

Blitheness became very popular on television since the 1950s, when goggle box sets started to become common in most adult countries. Cartoons were mainly programmed for children, on convenient fourth dimension slots, and especially U.s. youth spent many hours watching Saturday-morn cartoons. Many classic cartoons found a new life on the small-scale screen and by the end of the 1950s, the production of new animated cartoons started to shift from theatrical releases to Television serial. Hanna-Barbera Productions was particularly prolific and had huge hitting series, such as The Flintstones (1960–1966) (the start prime time blithe series), Scooby-Doo (since 1969) and Belgian co-product The Smurfs (1981–1989). The constraints of American television programming and the need for an enormous quantity resulted in cheaper and quicker limited animation methods and much more formulaic scripts. Quality dwindled until more than daring blitheness surfaced in the late 1980s and in the early 1990s with hit series such as The Simpsons (since 1989) every bit role of a "renaissance" of American animation.

While United states animated series also spawned successes internationally, many other countries produced their own child-oriented programming, relatively often preferring cease motion and puppetry over cel animation. Japanese anime TV series became very successful internationally since the 1960s, and European producers looking for affordable cel animators relatively often started co-productions with Japanese studios, resulting in hit series such as Barbapapa (The Netherlands/Nippon/France 1973–1977), Wickie und die starken Männer/小さなバイキング ビッケ (Vicky the Viking) (Republic of austria/Germany/Japan 1974), and The Jungle Volume (Italy/Nihon 1989).

Switch from cels to computers [edit]

Computer animation was gradually developed since the 1940s. 3D wireframe animation started popping up in the mainstream in the 1970s, with an early on (short) appearance in the sci-fi thriller Futureworld (1976).

The Rescuers Down Under was the first feature moving picture to exist completely created digitally without a photographic camera.[nine] It was produced in a style that's very like to traditional cel animation on the Reckoner Animation Product Organisation (CAPS), developed by The Walt Disney Company in collaboration with Pixar in the late 1980s.

The so-called 3D style, more frequently associated with computer animation, has become extremely pop since Pixar'due south Toy Story (1995), the first computer-animated characteristic in this way.

Most of the cel animation studios switched to producing mostly reckoner blithe films around the 1990s, as it proved cheaper and more profitable. Not only the very popular 3D animation manner was generated with computers, but also most of the films and series with a more than traditional hand-crafted appearance, in which the charming characteristics of cel blitheness could be emulated with software, while new digital tools helped developing new styles and effects.[10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15]

Economic condition [edit]

In 2010, the animation market place was estimated to be worth circa US$eighty billion.[xvi] By 2020, the value had increased to an estimated US$270 billion.[17] Animated feature-length films returned the highest gross margins (around 52%) of all film genres between 2004 and 2013.[18] Animation as an art and industry continues to thrive as of the early on 2020s.

Education, propaganda and commercials [edit]

The clarity of animation makes it a powerful tool for instruction, while its total malleability also allows exaggeration that can exist employed to convey potent emotions and to thwart reality. It has therefore been widely used for other purposes than mere entertainment.

During World War Ii, animation was widely exploited for propaganda. Many American studios, including Warner Bros. and Disney, lent their talents and their cartoon characters to convey to the public certain war values. Some countries, including Red china, Japan and the United Kingdom, produced their commencement feature-length animation for their war efforts.

Blitheness has been very pop in television commercials, both due to its graphic appeal, and the humour it can provide. Some animated characters in commercials have survived for decades, such as Snap, Crackle and Popular in advertisements for Kellogg'southward cereals.[19] The legendary animation director Tex Avery was the producer of the first Raid "Kills Bugs Dead" commercials in 1966, which were very successful for the company.[20]

Other media, trade and theme parks [edit]

Apart from their success in movie theaters and television series, many cartoon characters would too show extremely lucrative when licensed for all kinds of merchandise and for other media.

Animation has traditionally been very closely related to comic books. While many comic book characters found their way to the screen (which is often the case in Japan, where many manga are adapted into anime), original animated characters also commonly appear in comic books and magazines. Somewhat similarly, characters and plots for video games (an interactive blitheness medium) have been derived from films and vice versa.

Some of the original content produced for the screen can be used and marketed in other media. Stories and images can hands be adapted into children'due south books and other printed media. Songs and music take appeared on records and as streaming media.

While very many animation companies commercially exploit their creations outside moving epitome media, The Walt Disney Company is the best known and most extreme example. Since beginning being licensed for a children's writing tablet in 1929, their Mickey Mouse mascot has been depicted on an enormous corporeality of products, equally have many other Disney characters. This may have influenced some pejorative use of Mickey'due south name, but licensed Disney products sell well, and the and then-called Disneyana has many avid collectors, and even a dedicated Disneyana fanclub (since 1984).

Disneyland opened in 1955 and features many attractions that were based on Disney'southward drawing characters. Its enormous success spawned several other Disney theme parks and resorts. Disney's earnings from the theme parks have relatively often been college than those from their movies.

Criticism [edit]

Criticism of animation has been mutual in media and cinema since its inception. With its popularity, a big corporeality of criticism has arisen, especially animated feature-length films.[21] Many concerns of cultural representation, psychological effects on children have been brought up around the blitheness industry, which has remained rather politically unchanged and stagnant since its inception into mainstream civilization.[22]

Awards [edit]

As with whatsoever other form of media, blitheness has instituted awards for excellence in the field. Many are part of general or regional moving-picture show award programs, like the China'southward Gilded Rooster Award for Best Animation (since 1981). Awards programs dedicated to animation, with many categories, include ASIFA-Hollywood'due south Annie Awards, the Emile Awards in Europe and the Anima Mundi awards in Brazil.

University Awards [edit]

Apart from University Awards for Best Animated Short Moving-picture show (since 1932) and Best Animated Characteristic (since 2002), animated movies have been nominated and rewarded in other categories, relatively often for Best Original Vocal and All-time Original Score.

Dazzler and the Beast was the beginning animated film nominated for All-time Picture, in 1991. Up (2009) and Toy Story three (2010) also received Best Picture nominations, after the Academy expanded the number of nominees from five to ten.

Product [edit]

The cosmos of not-lilliputian animation works (i.e., longer than a few seconds) has developed as a form of filmmaking, with certain unique aspects.[23] Traits common to both live-action and animated feature-length films are labor intensity and high production costs.[24]

The most important difference is that once a film is in the production phase, the marginal price of 1 more shot is college for blithe films than live-activity films.[25] Information technology is relatively easy for a director to ask for one more than have during principal photography of a live-action film, only every take on an animated film must be manually rendered by animators (although the task of rendering slightly unlike takes has been made less tedious by modernistic computer animation).[26] It is pointless for a studio to pay the salaries of dozens of animators to spend weeks creating a visually dazzling five-infinitesimal scene if that scene fails to effectively accelerate the plot of the flick.[27] Thus, animation studios starting with Disney began the practice in the 1930s of maintaining story departments where storyboard artists develop every unmarried scene through storyboards, then handing the picture over to the animators just after the production team is satisfied that all the scenes make sense as a whole.[28] While live-action films are at present also storyboarded, they relish more latitude to depart from storyboards (i.e., real-fourth dimension improvisation).[29]

Some other trouble unique to animation is the requirement to maintain a movie's consistency from start to finish, even as films accept grown longer and teams have grown larger. Animators, like all artists, necessarily accept individual styles, but must subordinate their individuality in a consistent style to whatsoever style is employed on a particular pic.[xxx] Since the early 1980s, teams of about 500 to 600 people, of whom 50 to 70 are animators, typically have created feature-length animated films. It is relatively like shooting fish in a barrel for 2 or three artists to friction match their styles; synchronizing those of dozens of artists is more than difficult.[31]

This problem is commonly solved by having a separate group of visual development artists develop an overall wait and palette for each film before the animation begins. Grapheme designers on the visual development squad draw model sheets to show how each character should look similar with different facial expressions, posed in different positions, and viewed from different angles.[32] [33] On traditionally animated projects, maquettes were oft sculpted to further help the animators run across how characters would expect from different angles.[34] [32]

Unlike alive-activeness films, animated films were traditionally developed beyond the synopsis stage through the storyboard format; the storyboard artists would so receive credit for writing the film.[35] In the early 1960s, animation studios began hiring professional screenwriters to write screenplays (while also continuing to utilize story departments) and screenplays had go commonplace for animated films by the late 1980s.

Techniques [edit]

Traditional [edit]

Traditional animation (also called cel animation or paw-fatigued animation) was the process used for most blithe films of the 20th century.[36] The individual frames of a traditionally animated film are photographs of drawings, get-go fatigued on newspaper.[37] To create the illusion of movement, each drawing differs slightly from the one earlier information technology. The animators' drawings are traced or photocopied onto transparent acetate sheets called cels,[38] which are filled in with paints in assigned colors or tones on the side contrary the line drawings.[39] The completed graphic symbol cels are photographed one-past-one against a painted background by a rostrum camera onto motion-picture show film.[40]

The traditional cel blitheness procedure became obsolete by the kickoff of the 21st century. Today, animators' drawings and the backgrounds are either scanned into or drawn straight into a reckoner system.[1] [41] Various software programs are used to colour the drawings and simulate camera motility and effects.[42] The final animated piece is output to one of several delivery media, including traditional 35 mm picture show and newer media with digital video.[43] [1] The "look" of traditional cel blitheness is yet preserved, and the character animators' work has remained essentially the same over the by 70 years.[34] Some animation producers accept used the term "tradigital" (a play on the words "traditional" and "digital") to describe cel animation that uses meaning reckoner engineering.

Examples of traditionally animated feature films include Pinocchio (United States, 1940),[44] Animal Farm (Uk, 1954), Lucky and Zorba (Italy, 1998), and The Illusionist (British-French, 2010). Traditionally animated films produced with the aid of computer engineering science include The Lion Male monarch (US, 1994), The Prince of Arab republic of egypt (The states, 1998), Akira (Japan, 1988),[45] Spirited Away (Nippon, 2001), The Triplets of Belleville (French republic, 2003), and The Surreptitious of Kells (Irish gaelic-French-Belgian, 2009).

Full [edit]

Full animation refers to the process of producing high-quality traditionally animated films that regularly use detailed drawings and plausible move,[46] having a smooth blitheness.[47] Fully blithe films tin can be made in a variety of styles, from more realistically animated works like those produced by the Walt Disney studio (The Little Mermaid, Dazzler and the Beast, Aladdin, The Lion King) to the more 'cartoon' styles of the Warner Bros. animation studio. Many of the Disney animated features are examples of full animation, as are non-Disney works, The Undercover of NIMH (US, 1982), The Fe Behemothic (Usa, 1999), and Nocturna (Espana, 2007). Fully animated films are animated at 24 frames per second, with a combination of blitheness on ones and twos, meaning that drawings can exist held for ane frame out of 24 or two frames out of 24.[48]

Limited [edit]

Limited blitheness involves the apply of less detailed or more than stylized drawings and methods of movement usually a inclement or "skippy" motion animation.[49] Limited animation uses fewer drawings per second, thereby limiting the fluidity of the animation. This is a more than economical technique. Pioneered by the artists at the American studio United Productions of America,[fifty] express animation can be used as a method of stylized artistic expression, equally in Gerald McBoing-Boing (US, 1951), Yellow Submarine (UK, 1968), and sure anime produced in Nippon.[51] Its chief apply, however, has been in producing toll-effective animated content for media for boob tube (the work of Hanna-Barbera,[52] Filmation,[53] and other Television set animation studios[54]) and subsequently the Net (web cartoons).

Rotoscoping [edit]

Rotoscoping is a technique patented past Max Fleischer in 1917 where animators trace live-activity movement, frame by frame.[55] The source film tin be straight copied from actors' outlines into blithe drawings,[56] every bit in The Lord of the Rings (US, 1978), or used in a stylized and expressive way, every bit in Waking Life (US, 2001) and A Scanner Darkly (US, 2006). Some other examples are Burn down and Ice (US, 1983), Heavy Metal (1981), and Aku no Hana (Japan, 2013).

Live-action blending [edit]

Live-activeness/blitheness is a technique combining hand-drawn characters into live action shots or live-action actors into animated shots.[57] One of the earlier uses was in Koko the Clown when Koko was fatigued over live-activity footage.[58] Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks created a serial of Alice Comedies (1923–1927), in which a alive-action daughter enters an blithe world. Other examples include Allegro Not Troppo (Italian republic, 1976), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (U.s.a., 1988), Volere volare (Italy 1991), Space Jam (US, 1996) and Osmosis Jones (U.s., 2001).

Stop motion [edit]

Stop-motion blitheness is used to draw animation created by physically manipulating real-world objects and photographing them one frame of motion-picture show at a time to create the illusion of motility.[59] There are many dissimilar types of finish-motion animation, usually named after the medium used to create the animation.[sixty] Computer software is widely available to create this type of blitheness; traditional end-motion animation is commonly less expensive but more time-consuming to produce than current computer animation.[threescore]

- Puppet animation

- Typically involves terminate-motion puppet figures interacting in a constructed surroundings, in contrast to real-world interaction in model animation.[61] The puppets mostly accept an armature inside of them to keep them still and steady to constrain their movement to particular joints.[62] Examples include The Tale of the Fox (French republic, 1937), The Nightmare Earlier Christmas (United states, 1993), Corpse Bride (United states, 2005), Coraline (United states, 2009), the films of Jiří Trnka and the developed animated sketch-comedy television set series Robot Chicken (U.s., 2005–present).

- Puppetoon

- Created using techniques developed by George Pal,[63] are boob-animated films that typically use a different version of a puppet for unlike frames, rather than simply manipulating 1 existing puppet.[64]

A clay blitheness scene from a Finnish television commercial

- Clay animation or Plasticine animation

- (Often called claymation, which, however, is a trademarked name). It uses figures fabricated of clay or a similar malleable cloth to create terminate-move animation.[59] [65] The figures may have an armature or wire frame inside, like to the related puppet animation (beneath), that can be manipulated to pose the figures.[66] Alternatively, the figures may be made entirely of clay, in the films of Bruce Bickford, where clay creatures morph into a diversity of different shapes. Examples of dirt-animated works include The Gumby Show (U.s.a., 1957–1967), Mio Mao (Italy, 1974–2005), Morph shorts (Uk, 1977–2000), Wallace and Gromit shorts (UK, equally of 1989), Jan Švankmajer's Dimensions of Dialogue (Czechoslovakia, 1982), The Trap Door (Britain, 1984). Films include Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit, Chicken Run and The Adventures of Marking Twain.[67]

- Strata-cut animation

- Most commonly a grade of dirt animation in which a long staff of life-like "loaf" of dirt, internally packed tight and loaded with varying imagery, is sliced into thin sheets, with the blitheness camera taking a frame of the end of the loaf for each cut, eventually revealing the movement of the internal images within.[68]

- Cutout blitheness

- A type of stop-motion animation produced by moving 2-dimensional pieces of material paper or cloth.[69] Examples include Terry Gilliam'south animated sequences from Monty Python's Flying Circus (Uk, 1969–1974); Fantastic Planet (France/Czechoslovakia, 1973); Tale of Tales (Russia, 1979), The pilot episode of the developed television sitcom series (and sometimes in episodes) of S Park (U.s.a., 1997) and the music video Live for the moment, from Verona Riots band (produced by Alberto Serrano and Nívola Uyá, Spain 2014).

- Silhouette animation

- A variant of cutout animation in which the characters are backlit and only visible as silhouettes.[70] Examples include The Adventures of Prince Achmed (Weimar Democracy, 1926) and Princes et Princesses (French republic, 2000).

- Model animation

- Refers to stop-move blitheness created to interact with and exist equally a office of a live-activity world.[71] Intercutting, matte effects and split up screens are often employed to blend stop-motion characters or objects with alive actors and settings.[72] Examples include the work of Ray Harryhausen, equally seen in films, Jason and the Argonauts (1963),[73] and the work of Willis H. O'Brien on films, King Kong (1933).

- Go movement

- A variant of model blitheness that uses various techniques to create motion mistiness between frames of pic, which is not present in traditional cease motion.[74] The technique was invented by Industrial Calorie-free & Magic and Phil Tippett to create special effect scenes for the flick The Empire Strikes Back (1980).[75] Another instance is the dragon named "Vermithrax" from the 1981 motion picture Dragonslayer.[76]

- Object animation

- Refers to the utilise of regular inanimate objects in stop-motion animation, as opposed to especially created items.[77]

- Graphic blitheness

- Uses non-drawn flat visual graphic textile (photographs, paper clippings, magazines, etc.), which are sometimes manipulated frame by frame to create movement.[78] At other times, the graphics remain stationary, while the terminate-motion camera is moved to create on-screen activity.

- Brickfilm

- A subgenre of object animation involving using Lego or other similar brick toys to brand an animation.[79] [80] These take had a recent heave in popularity with the advent of video sharing sites, YouTube and the availability of cheap cameras and animation software.[81]

- Pixilation

- Involves the employ of live humans as stop-motion characters.[82] This allows for a number of surreal effects, including disappearances and reappearances, allowing people to appear to slide beyond the basis, and other furnishings.[82] Examples of pixilation include The Secret Adventures of Tom Thumb and Aroused Kid shorts, and the Academy Award-winning Neighbours by Norman McLaren.

Computer [edit]

Computer blitheness encompasses a multifariousness of techniques, the unifying cistron being that the animation is created digitally on a reckoner.[42] [83] second animation techniques tend to focus on image manipulation while 3D techniques usually build virtual worlds in which characters and objects motion and interact.[84] 3D animation tin create images that seem real to the viewer.[85]

2D [edit]

A 2D animation of two circles joined by a chain

second animation figures are created or edited on the calculator using second bitmap graphics and second vector graphics.[86] This includes automated computerized versions of traditional animation techniques, interpolated morphing,[87] onion skinning[88] and interpolated rotoscoping. 2D animation has many applications, including analog computer animation, Flash animation, and PowerPoint animation. Cinemagraphs are yet photographs in the class of an animated GIF file of which part is animated.[89]

Final line advection animation is a technique used in 2D animation,[90] to give artists and animators more influence and control over the final product every bit everything is washed within the aforementioned department.[91] Speaking about using this approach in Paperman, John Kahrs said that "Our animators can alter things, really erase away the CG underlayer if they desire, and change the profile of the arm."[92]

3D [edit]

3D animation is digitally modeled and manipulated by an animator. The 3D model maker usually starts past creating a 3D polygon mesh for the animator to manipulate.[93] A mesh typically includes many vertices that are continued by edges and faces, which requite the visual appearance of form to a 3D object or 3D surround.[93] Sometimes, the mesh is given an internal digital skeletal structure called an armature that can be used to command the mesh by weighting the vertices.[94] [95] This procedure is called rigging and tin be used in conjunction with key frames to create movement.[96]

Other techniques tin be applied, mathematical functions (e.1000., gravity, particle simulations), imitation fur or pilus, and effects, fire and water simulations.[97] These techniques fall under the category of 3D dynamics.[98]

Terms [edit]

- Cel-shaded animation is used to mimic traditional animation using reckoner software.[99] The shading looks stark, with less blending of colors. Examples include Skyland (2007, France), The Iron Behemothic (1999, United States), Futurama (1999, The states) Appleseed Ex Machina (2007, Japan), The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker (2002, Japan), The Fable of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (2017, Nihon)

- Machinima – Films created past screen capturing in video games and virtual worlds. The term originated from the software introduction in the 1980s demoscene, as well as the 1990s recordings of the showtime-person shooter video game Quake.

- Motility capture is used when live-action actors clothing special suits that allow computers to re-create their movements into CG characters.[100] [101] Examples include Polar Express (2004, The states), Beowulf (2007, US), A Christmas Carol (2009, US), The Adventures of Tintin (2011, US) kochadiiyan (2014, India)

- Computer blitheness is used primarily for animation that attempts to resemble real life, using advanced rendering that mimics in detail skin, plants, water, fire, clouds, etc.[102] Examples include Up (2009, United states of america), How to Train Your Dragon (2010, US)

- Physically based animation is blitheness using computer simulations.[103]

Mechanical [edit]

- Animatronics is the use of mechatronics to create machines that seem animate rather than robotic.

- Audio-Animatronics and Autonomatronics is a course of robotics animation, combined with three-D animation, created by Walt Disney Imagineering for shows and attractions at Disney theme parks move and brand noise (more often than not a recorded voice communication or vocal).[104] They are fixed to whatever supports them. They can sit down and stand, and they cannot walk. An Audio-Animatron is unlike from an android-type robot in that it uses prerecorded movements and sounds, rather than responding to external stimuli. In 2009, Disney created an interactive version of the engineering science called Autonomatronics.[105]

- Linear Animation Generator is a form of blitheness by using static moving-picture show frames installed in a tunnel or a shaft. The animation illusion is created by putting the viewer in a linear motion, parallel to the installed picture frames.[106] The concept and the technical solution were invented in 2007 past Mihai Girlovan in Romania.

- Chuckimation is a blazon of animation created by the makers of the television series Action League At present! in which characters/props are thrown, or chucked from off photographic camera or wiggled around to simulate talking by unseen hands.[107]

- The magic lantern used mechanical slides to project moving images, probably since Christiaan Huygens invented this early image projector in 1659.

Other [edit]

- Hydrotechnics: a technique that includes lights, h2o, fire, fog, and lasers, with high-definition projections on mist screens.

- Drawn on flick animation: a technique where footage is produced past creating the images directly on film stock; for instance, by Norman McLaren,[108] Len Lye and Stan Brakhage.

- Paint-on-glass blitheness: a technique for making animated films by manipulating slow drying oil paints on sheets of glass,[109] for example by Aleksandr Petrov.

- Erasure animation: a technique using traditional second media, photographed over time every bit the creative person manipulates the image. For case, William Kentridge is famous for his charcoal erasure films,[110] and Piotr Dumała for his auteur technique of animative scratches on plaster.

- Pinscreen animation: makes use of a screen filled with movable pins that can be moved in or out by pressing an object onto the screen.[111] The screen is lit from the side and then that the pins cast shadows. The technique has been used to create blithe films with a range of textural effects hard to achieve with traditional cel animation.[112]

- Sand animation: sand is moved around on a back- or front-lighted piece of glass to create each frame for an blithe picture show.[113] This creates an interesting effect when blithe because of the light dissimilarity.[114]

- Flip book: a flip book (sometimes, especially in British English, called a flick book) is a book with a series of pictures that vary gradually from ane page to the next, so that when the pages are turned apace, the pictures appear to animate by simulating move or another modify.[115] [116] Flip books are often illustrated books for children,[117] they also are geared towards adults and use a series of photographs rather than drawings. Flip books are not always split books, they announced as an added characteristic in ordinary books or magazines, often in the page corners.[115] Software packages and websites are also bachelor that convert digital video files into custom-fabricated flip books.[118]

- Character animation

- Multi-sketching

- Special furnishings animation

Run across besides [edit]

- Twelve basic principles of blitheness

- Animated war film

- Animation department

- Animated serial

- Architectural blitheness

- Avar

- Independent animation

- International Animation Day

- International Animated Pic Clan

- International Tournée of Animation

- List of pic-related topics

- Motility graphic design

- Society for Animation Studies

- Wire-frame model

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ a b c Buchan 2013.

- ^ "The definition of animation on dictionary.com".

- ^ Solomon 1989, p. 28.

- ^ Solomon 1989, p. 24.

- ^ Solomon 1989, p. 34.

- ^ Bendazzi 1994, p. 49.

- ^ * Total prior to 50th anniversary reissue: Culhane, John (12 July 1987). "'Snow White' At fifty: Undimmed Magic". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 June 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

By now, it has grossed nigh $330 million worldwide - so it remains one of the near popular films ever made.

- ^ * 1987 and 1993 grosses from N America: "Snow White and the 7 Dwarfs – Releases". Box Function Mojo. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

1987 release – $46,594,212; 1993 release – $41,634,471

- ^ "First fully digital characteristic moving picture". Guinness World Records. Guinness Earth Records Limited. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- ^ Amidi, Amid (1 June 2015). "Sergio Pablos Talks About His Stunning Hand-Drawn Project 'Klaus'". Cartoon Brew . Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ "The Origins of Klaus". YouTube. 10 October 2019. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ Bernstein, Abbie (25 February 2013). "Assignment Ten". Exclusive Interview: John Kahrs & Kristina Reed on PAPERMAN. Midnight Productions, Inc. Retrieved 6 Oct 2013.

- ^ "FIRST LOOK: Disney'southward 'Paperman' fuses hand-drawn amuse with digital depth". EW.com . Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ Sarto, Dan. "Within Disney's New Animated Brusk Paperman". Animation World Network. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ^ "Disney's Paperman animated short fuses CG and hand-drawn techniques". Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ Board of Investments 2009.

- ^ "Global blitheness market value 2017-2020". Statista . Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ McDuling 2014.

- ^ "Snap, Crackle, Popular® | Rice Krispies®". www.ricekrispies.com . Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ Taylor, Heather (10 June 2019). "The Raid Bugs: Characters Nosotros Beloved To Detest". PopIcon.life . Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ Amidi 2011.

- ^ Nagel 2008.

- ^ Laybourne 1998, p. 117.

- ^ Solomon 1989, p. 274.

- ^ White 2006, p. 151.

- ^ Laybourne 1998, p. 339.

- ^ Culhane 1990, p. 55.

- ^ Solomon 1989, p. 120.

- ^ Laybourne 1998, pp. 100–01.

- ^ Masson 2007, p. 94.

- ^ Beck 2004, p. 37.

- ^ a b Williams 2001, p. 34.

- ^ Culhane 1990, p. 146.

- ^ a b Williams 2001, pp. 52–57.

- ^ Laybourne 1998, pp. 99–100.

- ^ White 2006, p. 31.

- ^ Beckerman 2003, p. 153.

- ^ Thomas & Johnston 1981, pp. 277–79.

- ^ Laybourne 1998, p. 203.

- ^ White 2006, pp. 195–201.

- ^ White 2006, p. 394.

- ^ a b Culhane 1990, p. 296.

- ^ Laybourne 1998, pp. 35–36, 52–53.

- ^ Solomon 1989, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Beckerman 2003, p. 80.

- ^ Culhane 1990, p. 71.

- ^ Culhane 1990, pp. 194–95.

- ^ Laybourne 1998, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Beckerman 2003, p. 142.

- ^ Beckerman 2003, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Ledoux 1997, p. 24, 29.

- ^ Lawson & Persons 2004, p. 82.

- ^ Solomon 1989, p. 241.

- ^ Lawson & Persons 2004, p. xxi.

- ^ Crafton 1993, p. 158.

- ^ Laybourne 1998, pp. 163–64.

- ^ Laybourne 1998, pp. 162–63.

- ^ Beck 2004, pp. 18–nineteen.

- ^ a b Solomon 1989, p. 299.

- ^ a b Laybourne 1998, p. 159.

- ^ Solomon 1989, p. 171.

- ^ Laybourne 1998, pp. 155–56.

- ^ Beck 2004, p. 70.

- ^ Beck 2004, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Laybourne 1998, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Laybourne 1998, pp. 151–54.

- ^ Beck 2004, p. 250.

- ^ Furniss 1998, pp. 52–54.

- ^ Laybourne 1998, pp. 59–lx.

- ^ Culhane 1990, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Harryhausen & Dalton 2008, pp. ix–xi.

- ^ Harryhausen & Dalton 2008, pp. 222–26

- ^ Harryhausen & Dalton 2008, p. eighteen

- ^ Smith 1986, p. ninety.

- ^ Watercutter 2012.

- ^ Smith 1986, pp. 91–95.

- ^ Laybourne 1998, pp. 51–57.

- ^ Laybourne 1998, p. 128.

- ^ Paul 2005, pp. 357–63.

- ^ Herman 2014.

- ^ Haglund 2014.

- ^ a b Laybourne 1998, pp. 75–79.

- ^ Serenko 2007.

- ^ Masson 2007, p. 405.

- ^ Serenko 2007, p. 482.

- ^ Masson 2007, p. 165.

- ^ Sito 2013, pp. 32, lxx, 132.

- ^ Priebe 2006, pp. 71–72.

- ^ White 2006, p. 392.

- ^ Lowe & Schnotz 2008, pp. 246–47.

- ^ Masson 2007, pp. 127–28.

- ^ Beck 2012.

- ^ a b Masson 2007, p. 88.

- ^ Sito 2013, p. 208.

- ^ Masson 2007, pp. 78–80.

- ^ Sito 2013, p. 285.

- ^ Masson 2007, p. 96.

- ^ Lowe & Schnotz 2008, p. 92.

- ^ "Cel Shading: the Unsung Hero of Animation?". Animator Mag. 17 December 2011. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ Sito 2013, pp. 207–08.

- ^ Masson 2007, p. 204.

- ^ Parent 2007, p. 19.

- ^ Donald H. Firm; John C. Keyser (30 November 2016). Foundations of Physically Based Modeling and Animation. CRC Printing. ISBN978-one-315-35581-eight.

- ^ Pilling 1997, p. 249.

- ^ O'Keefe 2014.

- ^ Parent 2007, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Kenyon 1998.

- ^ Faber & Walters 2004, p. 1979.

- ^ Pilling 1997, p. 222.

- ^ Carbone 2010.

- ^ Neupert 2011.

- ^ Pilling 1997, p. 204.

- ^ Brown 2003, p. 7.

- ^ Furniss 1998, pp. 30–33.

- ^ a b Laybourne 1998, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Solomon 1989, pp. viii–x.

- ^ Laybourne 1998, p. xiv.

- ^ White 2006, p. 203.

Sources [edit]

Periodical manufactures [edit]

- Anderson, Joseph and Barbara (Spring 1993). "Journal of Moving-picture show and Video". The Myth of Persistence of Vision Revisited. 45 (1): iii–13. Archived from the original on 24 November 2009.

- Serenko, Alexander (2007). "Computers in Homo Behavior" (PDF). The Development of an Instrument to Measure out the Degree of Animation Predisposition of Agent Users. 23 (1): 478–95.

Books [edit]

- Baer, Eva (1983). Metalwork in Medieval Islamic Fine art. State University of New York Press. pp. 58, 86, 143, 151, 176, 201, 226, 243, 292, 304. ISBN978-0-87395-602-iv.

- Beck, Jerry (2004). Blitheness Art: From Pencil to Pixel, the History of Cartoon, Anime & CGI. Fulhamm London: Flame Tree Publishing. ISBN978-i-84451-140-2.

- Beckerman, Howard (2003). Blitheness: The Whole Story. Allworth Press. ISBN978-1-58115-301-9.

- Bendazzi, Giannalberto (1994). Cartoons: 1 Hundred Years of Cinema Animation . Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN978-0-253-20937-5.

- Buchan, Suzanne (2013). Pervasive Animation. New York and London: Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-80723-four.

- Canemaker, John (2005). Winsor McCay: His Life and Art (Revised ed.). Abrams Books. ISBN978-0-8109-5941-five.

- Cotte, Olivier (2007). Secrets of Oscar-winning Blitheness: Backside the scenes of 13 classic brusque animations. Focal Press. ISBN978-0240520704.

- Crafton, Donald (1993). Before Mickey: The Animated Film 1898–1928. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN978-0-226-11667-9.

- Culhane, Shamus (1990). Animation: Script to Screen. St. Martin's Printing. ISBN978-0-312-05052-viii.

- Drazin, Charles (2011). The Faber Book of French Cinema . Faber & Faber. ISBN978-0-571-21849-3.

- Faber, Liz; Walters, Helen (2004). Animation Unlimited: Innovative Short Films Since 1940 . London: Laurence Rex Publishing. ISBN978-ane-85669-346-2.

- Finkielman, Jorge (2004). The Film Industry in Argentina: An Illustrated Cultural History. North Carolina: McFarland. p. 20. ISBN978-0-7864-1628-eight.

- Furniss, Maureen (1998). Art in Motility: Blitheness Aesthetics. Indiana University Press. ISBN978-i-86462-039-nine.

- Godfrey, Bob; Jackson, Anna (1974). The Do-It-Yourself Film Blitheness Book. BBC Publications. ISBN978-0-563-10829-0.

- Harryhausen, Ray; Dalton, Tony (2008). A Century of Model Animation: From Méliès to Aardman. Aurum Press. ISBN978-0-8230-9980-1.

- Herman, Sarah (2014). Brick Flicks: A Comprehensive Guide to Making Your Own Stop-Motion LEGO Movies. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN978-one-62914-649-2.

- Lawson, Tim; Persons, Alisa (2004). The Magic Behind the Voices [A Who'due south Who of Cartoon Voice Actors]. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN978-1-57806-696-4.

- Laybourne, Kit (1998). The Animation Volume: A Complete Guide to Animated Filmmaking – from Flip-books to Sound Cartoons to iii-D Animation. New York: 3 Rivers Printing. ISBN978-0-517-88602-ane.

- Ledoux, Trish (1997). Complete Anime Guide: Japanese Animation Moving-picture show Directory and Resource Guide. Tiger Mountain Printing. ISBN978-0-9649542-5-0.

- Lowe, Richard; Schnotz, Wolfgang, eds. (2008). Learning with Animation. Research implications for design. New York: Cambridge University Printing. ISBN978-0-521-85189-three.

- Masson, Terrence (2007). CG101: A Calculator Graphics Industry Reference. Unique and personal histories of early computer animation production, plus a comprehensive foundation of the industry for all reading levels. Williamstown, MA: Digital Fauxtography. ISBN978-0-9778710-0-1.

- Needham, Joseph (1962). "Science and Culture in Cathay". Physics and Concrete Applied science. Vol. IV. Cambridge University Printing.

- Neupert, Richard (2011). French Animation History. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN978-1-4443-3836-2.

- Parent, Rick (2007). Reckoner Blitheness: Algorithms & Techniques. Ohio State University: Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN978-0-12-532000-ix.

- Paul, Joshua (2005). Digital Video Hacks. O'Reilly Media. ISBN978-0-596-00946-5.

- Pilling, Jayne (1997). Society of Animation Studies (ed.). A Reader in Animation Studies. Indiana University Printing. ISBN978-1-86462-000-ix.

- Priebe, Ken A. (2006). The Art of Stop-Movement Animation. Thompson Grade Technology. ISBN978-one-59863-244-6.

- Rojas, Carlos; Chow, Eileen (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas. Oxford University Printing. ISBN978-0-xix-998844-0.

- Sammond, Nicholas (27 August 2015). Birth of an Industry: Blackface Minstrelsy and the Ascent of American Blitheness. Durham, NC: Knuckles University Printing. doi:10.1515/9780822375784. ISBN9780822358527. OCLC 8605897837.

- Shaffer, Joshua C. (2010). Discovering The Magic Kingdom: An Unofficial Disneyland Holiday Guide. Indiana: Author House. ISBN978-1-4520-6312-half dozen.

- Sito, Tom (2013). Moving Innovation: A History of Computer Animation. Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN978-0-262-01909-5.

- Solomon, Charles (1989). Enchanted Drawings: The History of Blitheness. New York: Random House, Inc. ISBN978-0-394-54684-1.

- Thomas, Bob (1958). Walt Disney, the Fine art of Animation: The Story of the Disney Studio Contribution to a New Art. Walt Disney Studios. Simon and Schuster.

- Thomas, Frank; Johnston, Ollie (1981). Disney Blitheness: The Illusion of Life. Abbeville Printing. ISBN978-0-89659-233-9.

- Smith, Thomas G. (1986). Industrial Light & Magic: The Art of Special Effects. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN978-0-345-32263-0.

- White, Tony (2006). Animation from Pencils to Pixels: Classical Techniques for the Digital Animator. Milton Park: Taylor & Francis. ISBN978-0-240-80670-ix.

- Williams, Richard (2001). The Animator's Survival Kit. Faber and Faber. ISBN978-0-571-20228-7.

- Zielinski, Siegfried (1999). Audiovisions: Movie theatre and Television as Entr'actes in History. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN978-90-5356-303-eight.

Online sources [edit]

- Amidi, Amid (2 December 2011). "NY Film Critics Didn't like a Single Animated Film This Yr". Cartoon Mash. Retrieved 19 Feb 2016.

- Ball, Ryan (12 March 2008). "Oldest Animation Discovered in Iran". Blitheness Magazine . Retrieved fifteen March 2016.

- Beck, Jerry (2 July 2012). "A Little More About Disney's "Paperman"". Cartoon Brew.

- Bendazzi, Giannalberto (1996). "The Untold Story of Argentine republic's Pioneer Animator". Animation World Network. Retrieved 29 Apr 2016.

- "Animation" (PDF). boi.gov.ph. Lath of Investments. Nov 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- Brown, Margery (2003). "Experimental Animation Techniques" (PDF). Olympia, WA: Evergreen State Collage. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2008. Retrieved eleven November 2005.

- Carbone, Ken (24 Feb 2010). "Stone-Historic period Animation in a Digital World: William Kentridge at MoMA". Fast Company . Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Haglund, David (vii Feb 2014). "The Oldest Known LEGO Movie". Slate . Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- "World's Oldest Animation?". theheritagetrust.wordpress.com. The Heritage Trust. 25 July 2012. Archived from the original on 22 October 2015.

- Kenyon, Heather (1 February 1998). "How'd They Do That?: Finish-Motion Secrets Revealed". Blitheness Globe Network. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- Nagel, Jan (21 May 2008). "Gender in Media: Females Don't Dominion". Animation Earth Network. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- McDuling, John (3 July 2014). "Hollywood Is Giving Up on Comedy". The Atlantic. The Atlantic Monthly Group. Retrieved twenty July 2014.

- McLaughlin, Dan (2001). "A Rather Incomplete But Even so Fascinating". Movie TV. UCLA. Archived from the original on 19 November 2009. Retrieved 12 Feb 2013.

- O'Keefe, Matt (11 November 2014). "6 Major Innovations That Sprung from the Heads of Disney Imagineers". Theme Park Tourist. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- Watercutter, Angela (24 May 2012). "35 Years After Star Wars, Effects Whiz Phil Tippett Is Slowly Crafting a Mad God". Wired . Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Zohn, Patricia (28 February 2010). "Coloring the Kingdom". Vanity Fair . Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- "Walt Disney'due south Oscars". The Walt Disney Family Museum. 22 Feb 2013. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- "Władysław Starewicz – Biography". civilisation.pl. Adam Mickiewicz Institute. 16 April 2012. Retrieved nine February 2016.

External links [edit]

- The making of an 8-minute cartoon brusque

- "Animando", a 12-minute film demonstrating 10 different animation techniques (and teaching how to apply them).

- Bibliography on blitheness – Websiite "Histoire de la télévision"

- Animation at Curlie

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Animation

Posted by: mcnamaragulay1979.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Does It Mean To Animate On Twos"

Post a Comment